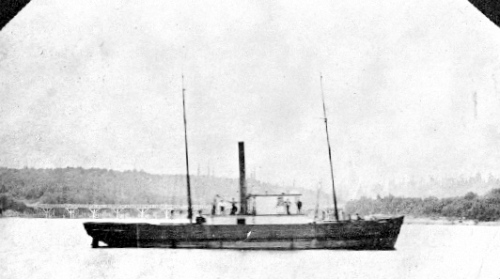

In early British Columbia, nautical disasters were common occurrences.One of the 120 vessels sunk or damaged in the Seymour Narrows off of Vancouver Island was the Grappler,a former colonial navy gunboat turned cargo freighter, which sank on April 28th 1883, near Duncan Bay. Islander author T.W. Patterson describes Grappler’s fate.

Her captain was John T. Jaegers, a seasoned mariner and well known local captain. In the article, Patterson provides some background details about the captain. After arriving in Victoria aboard the vessel Gondolier in the late 1870’s, Jaegers acted as mate aboard the Hudson’s Bay Company steamer Beaver under Captain J.D. Warren, until he himself was given command of the ship, which he captained for a further three years. After more than twenty years as a mariner on the B.C. coast, he was forced to retire from his command of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company Steamer R.P. Rithet, when he was diagnosed with cancer. He succumbed to the disease, and “crossed the bar” in September of 1898.

However, in April of 1883, Jaegers was in command of the ill-fated freighter Grappler and carrying a load of gunpowder, cannery supplies and a 100 chinese cannery workers on a return trip from Naniamo. Soon after the Grappler left Naniamo trouble started.

Late that night, the Grappler passed Duncan Bay in calm seas. All was peaceful until engineer William Steele smelled smoke. Moments later, he passed the terrifying word to Capt. Jaegers that there was a fire in the forward hold.

By the time Jaegers and his mate, John Smith, were able to have coal cleared from ‘tweendecks thereby enabling them to reach the forward hold, they knew that the fire was well established. After ordering that all hatches be sealed, Captain Jaegers returned from the wheel house and gave four, sharp blasts from his whistle in the vain hope that someone ashore might be alerted to the Grapplers danger.

Then, as mate Smith and a deckhand attempted to fight the blaze with a single hose, Jaegers tried to head the dying steamer towards shore.

In spite of the captain and crew’s best efforts both attempts to avert the catastrophe failed. When the steering cables broke, the ship went out of control, steering spasmodically all by itself. This caused it to gain speed, which in turn fanned the flames and caused the Grappler to become a blazing inferno. The Colonist reported:

“The heavy engines, racing at full speed, were siding with the work of death and destruction by forcing the doomed craft through the water with a rapidity which made the lowering of a boat an impossibility. If one reached the water without swamping, the crazed Chinese at once loaded it with rice and personal effects, on top of which they piled in such numbers that it immediately went down.”

In the last few moments before the ship sank, Captain Jaegers resolutely remained at his post, he was forced to flee only when the forward deck of the Grappler collapsed. At the very last moment he jumped over the side and swam as hard as he could for the shore.

His ordeal was not ended, as the tide “carr[ied] him down [the shoreline] at a frightful rate, but at last with a despairing effort he reached an eddy which deposited him on a huge boulder, leaving him there unconscious.”

Many other passengers were not so lucky. A large majority of the ships passengers and crew either drowned when they tried to launch a boat and escape, or burned with the Grappler. Patterson states the death toll to be close to 89 people, however, more conservative estimates state that it was likely closer to between 71 and 77. It is highly probable that the majority of the people who died where Chinese cannery workers.

Although he was originally presumed dead, captain Jaegers survived the ship wreck, and was rescued by a group of loggers. He went on to work for the Canadian pacific Navigation Co. until his death in 1898.